In his recent book Sarn Helen: A Journey Through Wales, Past, Present and Future, Tom Bullough walks an old Roman way between North and South Wales to reflect on the state of the nation and, especially, its “skeletal landscape” during an era of global nature decline and climate change, or as the Guardian put it “environmental end times.” Despite his own Welsh hill farming background, Bullough expresses particular concern about a tendency for sheep monoculture in Mid Wales, and it therefore seems a good time to reflect on ‘man-made’ landscape history in the present day counties of Powys and Ceredigion. This post will focus on the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods and the influence of religious orders, notably Cistercians, and uchelwyr (nobility) on a land-based economy arguably somewhat more diverse than today’s. The account also provides some further historical background to the previous blog discussion about Tudor royal horse-breeding at Caersws and its hinterland. However, on this occasion the journey begins in Strata Florida, one of the most powerful and important religious (plus strategic) centres in Wales until the abbey’s dissolution by Henry VIII when much of the former monastic lands were given to the statesman Thomas Cromwell, famously brought back to life again in the novel trilogy of Hilary Mantel.

Cistercians and Strata Florida

A 2015 article by Lieutenant-General Jonathon Riley in The Welsh History Review (available on the Generalship website) considers The Military Garrisons of Henry IV and Henry V at Strata Florida, 1407 and 1415-16. The author states: “The garrison of 1407 was a punitive force during the closing stages of Glyndwr’s rebellion; that of 1415 was to suppress possible dissent during the absence of Henry V in the Agincourt campaign.” Of Strata Florida’s economic and wider strategic importance, he writes:

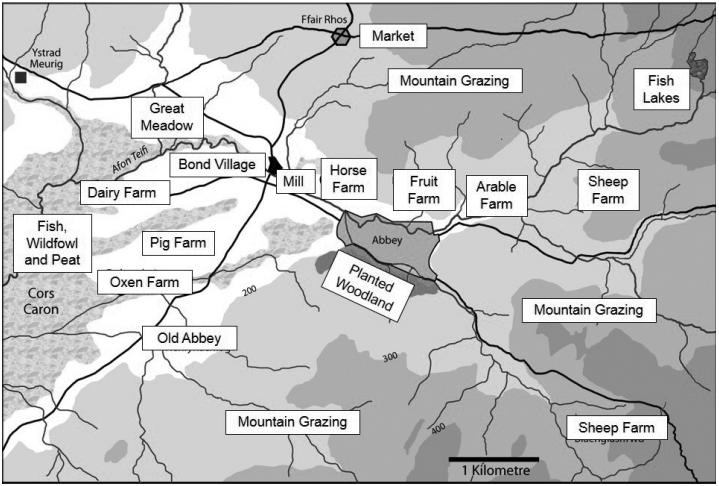

The abbey lands were located on the southern frontier of what had recently been – maybe still was – bandit country. It lay on the very westernmost edge of the Cambrian Mountains, at the head of the valley of the River Teifi which ran south and west into the Irish Sea at Cardigan, nearly sixty miles away. Between the abbey and the sea lay a strip more than ten miles wide on the north bank of the Teifi, some of it marsh, like the great bog of Tregaron, but much of it fine agricultural land suitable for mixed farming. To the east, the uplands provided valuable summer pastures for sheep, cattle and ponies as well as slate, building stone, silver, lead and copper: the Cistercians were well known as sponsors of major medieval industrial complexes working metal. Tracts of this upland had been ceded in previous centuries to the military orders to provide income for the upkeep of the Christian kingdoms of Outremer in the Holy Land – hence the place names that still endure: Ysbyty Ystwyth for the Hospitallers, Temple Bar for the Templars. All this meant a money-based economy, and as elsewhere in medieval Europe, the Cistercians were the bankers who serviced this economy…..

Outremer is a term used to describe European ‘crusader states’ in the Middle East between 1098-1291. However, according to one assessment, “it was as agriculturists and horse and cattle breeders that the Cistercians exercised their chief influence on the progress of civilisation in the Middle Ages.” Whilst this judgement by posterity might not recognise the significant religious and cultural legacy of Strata Florida, it does seem to chime with key interests of the abbey as reported by Gerald of Wales during his travels in the late 12th century. Nevertheless, it was the horses of Powys that most impressed Gerald.

Horses, War and Religion

In this third district of Wales, called Powys, there are most excellent studs put apart for breeding, and deriving their origin from some fine Spanish horses, which Robert de Belesme, earl of Shrewsbury, brought into this country: on which account the horses sent from hence are remarkable for their majestic proportion and astonishing fleetness. Gerald of Wales

Whilst the above account unsurprisingly suggests that warfare was the key spur for horse breeding in the Middle Ages – a theme explored in depth by the Medieval Warhorse project – the evidence below indicates the Powys Cistercian abbeys of Cwm Hir and Strata Marcella probably bred animals for a range of uses. The following description is also likely to reflect the monastic horse business in Mid Wales.

Horse breeding and trading was evidently a specialism of the Yorkshire Cistercian houses and the White Monks here were renowned for their quality. The superiority of their horses was clearly appreciated in royal circles, for in 1236 Henry III requested two palfreys, stipulating that these should be of northern parts, good and fit – he received one from Rievaulx and one from Jervaulx. The attraction of owning one of these quality horses may have encouraged donors to grant land to the abbey. This was the case at Furness, where a donor requested an honourable horse in return for his generosity to the community.

Indeed, a website dedicated to the life and work of late Medieval Welsh poet Guto’r Glyn has a page which points to the equestrian patronage of Dafydd ab Owain, presumably at that time Abbot of Strata Marcella. He is celebrated in the following poem extract along with the abbey’s prosperous landholdings at Ystrad Marchell which roughly co-incides with the parish of Welshpool (‘Y Trallwng’ in Welsh).

Ni bu dir yn y byd well,

Bwyd meirch lle bu ŷd Marchell,

Gwenithdir, gweirdir a gwŷdd,

A galw ’dd wyf Arglwydd Ddafydd….

Never was there better land in the world,

horse-fodder where Marcella’s corn used to grow,

land for growing wheat, land for growing grass and trees,

and I call Lord Dafydd….. (poem 115.13-16)

The ‘Horses’ page is also interesting in the different words for horses used by Guto’r in another poem: “Several terms are used in the poem to refer to the animal requested, namely: march, gorwydd, eddestr, and planc… Hacnai is a borrowing from English and denotes a horse of middling size or a riding horse.” Meanwhile, the significant number of poems addressed to Dafydd ab Owain by Guto’r and other poets requesting gifts of horses seem to underline the abbot’s (later bishop) position as a notable breeder.

Some Concluding Thoughts

The Sws Way (Sarn Sws) was an ancient Roman trackway that reputedly ran from Brecon in modern day South Powys to Caersws in North Powys and thence across the English border to Chester, although only evidence for the northern section of the route is available. Like Caersws, Brecon was a major Roman military outpost according to CADW “manned by highly trained legionaries of the Vettonian Spanish Cavalry Regiment.” It is therefore possible that the influence of Spanish and other European horse breeds on Welsh (and British more generally) stock predates the Medieval period and may even be pre-Roman. Moreover, “the linguist John Rhys noted that the dialect of Mid-Wales Welsh (Y Bowyseg) was closer to the Gaulish language than its neighbours, and concluded that the area had pre-Roman links to Gaul.” (See Wikipedia entry for Caersws) Clearly not speculation is the strategic location of the village which has made it an important centre during various historical periods. The preceding discussion and the earlier post on the location of a royal horse stud in the area during the Tudor dynasty reflect this position.

Etymology and toponymy can pose both a challenge and opportunity for historical research and those of Eskermayne and, indeed, Caersws itself (a fitting subject for another blog!) make interesting case studies. A January 2023 webinar led by Dr Dylan Foster Evans of the Welsh Place-Name Society for the Cambrian Mountains Society highlights prevalence of the word ‘esgair’ (ridge or ‘esker’). Meanwhile, the etymology of ‘maen’ (stone) is explored here. Whilst Esgair Maen (Anglicised form Eskermayne) is used to denote individual place names in the Cambrian Mountains hinterland near Strata Florida and Llanidloes, for instance – and gives title to part of the Robert Dudley estate discussed previously – it is also possible that the name might have been used to describe a wider landscape of stone ridges which included the Park estate near Caersws. A recent helpful email exchange with Professor Robert Liddiard of the Medieval Warhorse project confirms the probability that the Park and Eskermayne studs were one and the same, based on various accounts for stock numbers of around 100 (or, more precisely, 97 mares, 11 fillies, and 4 colts for Eskermayne in 1547). It is also possible that the ‘unknown’ location of another Tudor royal horse breeding site in Wales might coincide with the former landholdings and equestrian operations of Cistercian abbeys in Mid Wales, including the granges of Strata Marcella, Cwm Hir and Strata Florida. What is certainly the case is the regional land-based economy of the Medieval and Earl Modern periods was highly diverse and dynamic, with horses playing a vital role. Returning to R J Moore-Colyer’s account of Montgomeryshire horses, the lasting impression is quite magical although, sadly, around Caersws the animals have long disappeared.

The native ponies, for centuries known as ‘merlins’, ran virtually wild on the hills….