Who set the wild donkey free?

Who loosed the bonds of the onager,

Whose home I have made the wilderness,

And the barren land his dwelling?

He scorns the tumult of the city;

He does not heed the shouts of the driver.

The range of the mountains is his pasture,

And he searches after every green thing.

Yahweh in The Book of Job, New King James Bible

This post revisits potential roles for equids (horses and donkeys) in nature conservation, previously considered in a 2020 ECOS article where the focus was on extensive grazing in Britain but with reference to the equine programmes of Rewilding Europe. The perspective here is more global, and primarily seeks to distinguish between wild and feral animals, re-introduced species, ‘primitive’ horses, landraces and domesticated breeds, together with some key issues for their management in a range of nature conservation and restoration environments. A better understanding of equine natural history and equestrian heritage is advocated to support more informed discussions about animal and landscape management programmes, as well as sustainable grazing for recreational equids.

Nature and ‘Management’

Millennia before Yahweh, the original god of Middle Eastern monotheism, identified the onager as a wild equid, Aboriginal peoples were managing ‘wilderness’ areas. Human interventions in the landscape, including that of Old Testament West Asia, and influence on animal populations extend from prehistory to the present. Given the importance of free ranging equids as a food source for humans prior and after domestication, such interventions will have influenced equine natural history. Moreover, equids are regarded as having a key role in the development of pastoralism. Now in regions such as Northern Kenya, management of wild animal populations, including zebra, is increasingly co-dependent on sustainable livestock grazing.

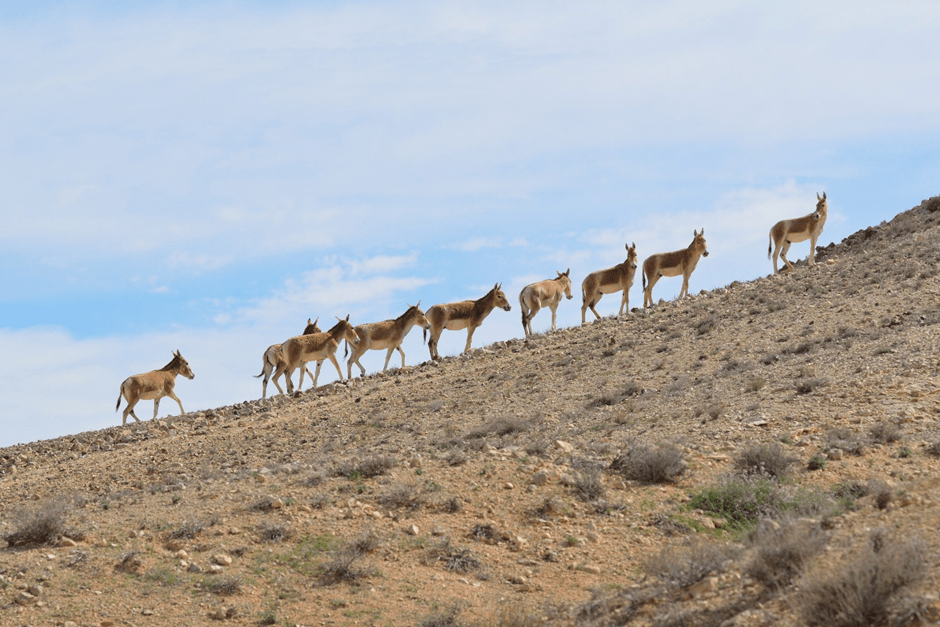

Wild Equids: Onager and Zebras

The onager is closely related to the African wild ass, as they both share the same ancestor. There are now probably less than 600 of the latter in the wild, with the species listed as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. As with zebra, competition with livestock for grazing and water supplies, along with hunting for food and traditional medicines, pose major threats notwithstanding their protected status. Whilst the Asian wild ass or onager has fared better, one of five sub-species (the Syrian wild ass) is now extinct, two are endangered, and two are near threatened. Habitat loss is the main reason for decline in populations. The onager formerly had a wide territorial range from Europe across south west, central and northern Asia. Typically, onagers live in hot and cold deserts together with other arid and semi-arid regions, including grassland plains, steppes and savannahs. Persian onagers are currently being reintroduced in the Middle East as replacements for the extinct Syrian wild ass in the Arabian Peninsula, Israel and Jordan. Similarly, Rewilding Europe has a re-introduction project for onager (kulan) in the steppe of southern Ukraine. Kiang are genetically distinct species of wild ass native to the Tibetan Plateau, Ladakh and Northern Nepal with most distribution in China.

There are three living species of zebra: the Grévy’s zebra, plains zebra, and the mountain zebra. Zebras share the genus Equus with horses and asses, the three groups being the only surviving members of the family Equidae. The IUCN lists the Grévy’s zebra as endangered, the mountain zebra as vulnerable and the plains zebra as near-threatened. Grévy’s zebra populations, although stable, are estimated to include less than 2,000 mature individuals. Mountain zebras number approximately 35,000 individuals and their population seems to be increasing. Plains zebra are estimated to number some 150,000–250,000 with a decreasing population trend. Human intervention has fragmented zebra ranges and they are threatened by habitat destruction and hunting for their hide and meat. Zebra also compete with livestock and fences obstruct their territories. In addition, civil wars in some countries have caused populations declines. Zebras are native to eastern and southern Africa and live in a variety of habitats such as savannahs, grasslands, woodlands, shrublands, and mountainous areas.

Feral Horses and Donkeys

The term ‘feral’ (and semi-feral) is used here to describe animals that have ‘rewilded’ themselves following domestication. They are not the genuinely wild equids described previously, or the re-introduced ‘primitive’ Przewalski’s horse described below. ‘Free-roaming’ is a term sometimes applied to both feral and deliberately rewilded horses and donkeys. For instance, current research by The Donkey Sanctuary notes that: “The emergence of free-roaming donkey populations has brought novel challenges for conservationists, land managers and animal welfarists alike. In many places they are categorised as ‘non-native’ and so framed as illegitimate and ‘out of place.’” An example of the latter categorisation is the use of ‘invasive species’ to describe feral horse and donkey populations in Australia, where they are widespread. Although equids are non-native to Australia, there are very different views on how they should be managed with animal welfare and compassionate conservation agendas increasingly cited, along with claims that feral horses and donkeys are now part of local ecosystems. Elsewhere, including Saudi Arabia, feral donkeys have been identified as ‘pests’ when they occupy the former range of wild ancestors. By comparison, both free-ranging and formerly domesticated equids are welcome and regarded as important ‘heritage’ in some countries, including North Cyprus and Namibia.

Natural adaptation of semi-wild or feral equids is sometimes associated with the development of distinctive ‘ecotypes‘ However, the term is still relatively undefined for equine application, as is the relationship between this and ‘landrace’ (see below). An example of its usage can be found in this account of Serrano horses involved in rewilding the Iberian Highlands.

Re-introduced ‘Primitive’ Horses

Przewalski’s horse is generally accepted as the only genuine ‘primitive’ or wild surviving equid. However, Rewilding Europe are working to create a formal (administrative) ‘status wild’ for others horses, including Konik, used in nature conservation and restoration programmes. Whilst Koniks are now strongly associated with European rewilding and similar projects, largely because of recent unregulated breeding and plentiful supply, they are the progeny of deliberate breeding from a small founder population in Poland during the early 20th century. By contrast, Przewalski’s horse, also known as the Mongolian wild horse, Dzungarian horse or takhi, is a rare and endangered equid originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. Once extinct in the wild, it has been reintroduced to its native habitat since the 1990s in Mongolia at the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal Nature Reserve, and Khomiin Tal, as well as several other locales in Central Asia and Eastern Europe, including the Chernobyl Radiological and Ecological Biosphere Reserve. Nevertheless, the primitive status of Przewalki’s horse was challenged in 2018 when DNA analysis of equine remains associated with the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia revealed the animals were of Przewalski lineage, although the domestication status of these animals is questioned. Still, there remains a case for the Botai culture as a major user of domestic horses by about 3,500 BC, nearly 1,000 years earlier than the previous scientific consensus.

Landraces and Heritage Breeds

There is a useful discussion of the differences between landraces and horse breeds in the June 2018 issue of the US magazine EQUUS. Whilst these differences may not be as clear cut as the article suggests – the Exmoor pony is a case in point – it may still be useful to consider ‘landraces’ as “a population of feral horses that has adapted to its natural and cultural environment over time”. In Wales, this include semi-feral populations of hill ponies, such as those found in the Carneddau Mountains These are distinct from the Welsh Mountain Pony breed. The Exmoor pony, on the other hand, is described as both a landrace and a breed, and considered by some experts* as perhaps the closest surviving ancestor of the wild horse in Europe. As their names suggest, Carneddau and Exmoor ponies, along with other hardy native breeds, are strongly identified with the mountains and moorlands of the British Isles, including Ireland. Along with their habitats, including national parks and other protected areas, they are, therefore, regarded by many as an important part of our national heritage. However, this has not always been fully understood or recognised by groups involved in nature conservation and restoration who have introduced Konik horses (see above) without due consideration.

Further discussion of the natural history of the Exmoor pony can be found in this article: Baker S, Greig C, Macgregor H and Swan A (1998) Exmoor ponies – Britain’s prehistoric wild horses? British Wildlife, 9 (5), 304-313 as well as *Dr Sue Baker’s book Exmoor Ponies Survival of the Fittest – A Natural History

Sustainable Equine Grazing

Although the preceding reference to the use of Koniks for conservation grazing and nature restoration projects in Britain may imply criticism, this is rather intended as a caveat about the need to better acknowledge the natural heritage importance of British mountain and moorland ponies. In fact, there may be practical and welfare reasons for the employment of Koniks arising from their relative ease of acquisition and management (an important consideration for smaller nature conservation groups) and, possibly, reduced vulnerability to grazing-related health conditions such as laminitis and grass sickness Nevertheless, at the present time comparative research on British native ponies and Konik horses is lacking, mainly due to shortage of funding. In the meantime, greatly increased media coverage of climate change and nature decline is finally registering with more organisations and individuals involved in keeping horses for their main contemporary purpose of recreation in Western countries. For instance, the University of Liverpool has recently conducted An Exploration of Environmentally Sustainable Practices Associated with Alternative Grazing Management System Use for Horses, Ponies, Donkeys and Mules in the UK which notes that “equestrian grazing management is a poorly researched area, despite potentially significant environmental impacts.” What is certainly obvious is that many horses could be managed and grazed more sustainably for their own benefit and that of the environment.

Some Concluding Reflections

As mentioned at its beginning, this post revisits a 2020 ECOS article on the use of equids for extensive grazing (in nature conservation, restoration, rewilding etc) mainly in Britain, and then locates this theme within a broader global context to provide a better understanding of equine natural history and equestrian heritage. The subsequent narrative demonstrates the importance of wild asses in this context, the existence of only one species of genuinely wild horse, and the need for a more comprehensive overview of feral horses and donkeys where these are both generally welcomed or regarded as invasive species. A distinction is again made between European Konik horses and British native landraces and heritage breeds associated with mountain and moorland environments. Also, since the 2020 article further research has been carried out on measuring the welfare of free-roaming horses. Finally, the need for more sustainable grazing in the management of equids kept for recreation is highlighted. The latter requires greater collaboration and co-operation between environmental and equestrian stakeholders, particularly educators, with the proviso that equine matters are sometimes contentious.

Horses for a quarrel. Camels for the desert., And oxen for poverty. Arab proverb

Postscript February 2023: Excellent BBC Radio 3 Free Thinking podcast on the cultural significance of donkeys, including their increasing role in wellbeing programmes for children and adults, which also emphasises the animals’ continued economic importance in many developing countries.