This blog launched in March 2021 with a post on the Severn Valley Water Management Scheme promoted by the River Severn Partnership as part of a proposed Severn Regional Growth Zone. Like the majority of major spatial programmes, these initiatives at first met with significant public opposition and scepticism, not least with regard to the proposal for a combined Shrewsbury dam and relief road which was subsequently dropped. This post will consider how large-scale programmes involving landscape, built environment and spatial regeneration might be better integrated and communicated to stakeholders, including the public. The starting point is a consideration of what is meant by the term ‘regeneration’ in the three contexts identified. Two case studies are then considered: the proposed Severn Regional Growth Zone and a mooted Cambrian Regeneration Zone for Mid Wales. The potential relevance and application of ‘integrated regeneration’ is then considered for Ukraine’s post-war recovery.

Landscape Regeneration

The concept of ‘landscape regeneration’ is, on the one hand, a potential extension of spatial planning and, on the other, a much-needed means of restoring land use principles to the practice of area-based (now usually called development) planning in Britain. Like many novel ideas, it is not at present either fully defined or widely understood but a recently-established Centre for Landscape Regeneration at Cambridge University offers some very helpful insights. CLR’s mission is “to provide the knowledge and tools needed to regenerate the British countryside using cost-effective nature-based solutions that harness the power of ecosystems to provide broad societal benefits including biodiversity recovery and climate mitigation and adaptation.” Similarly, the Devon Environment Foundation locates landscape regeneration within a broad range of “initiatives such as regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, rewilding, tree planting, meadow restoration, peatland conservation and restoration, eco tourism, wildlife safaris, and much more.” Both Cambridgeshire and Devon are also pilot areas for a new land use framework approach promoted by the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, later recommended for rollout in England in a House of Lords report.

Built Environment Contexts

‘Urban regeneration’ (or reconstruction as it was known in the mid-20th century) is historically linked to programmes to re-build towns and, particularly, major cities devastated by World War II. Many re-constructed European city centres are still regarded as outstanding examples of this. However, for various reasons, including lack of high quality public transport provision, the process was widely considered to be less successful in Britain’s large urban areas, partly contributing to their decline by the 1970s. This was subsequently much hastened by de-industrialisation which, combined with the development of container ports, created vast inner city wastelands in places like Liverpool and London Docklands. The term ‘regeneration’ started to be applied during this period and has since become a multi-disciplinary focus for policy and practical interventions in the built environment and local economy in an ever-increasing range of international contexts. However, there has also been a tendency for urban regeneration to return to its classical roots in re-construction with the expression ‘place-making” now often deployed, alongside ‘urban design,’ sometimes provoking aesthetic debates. There have also been specific criticisms of so-called ‘prettification’ schemes in ‘left-behind’ communities and wider critiques of the unsustainability of much development, particularly in its prevailing form of urban sprawl.

Spatial Planning Dimension

Northern European planning has tended to have both a strategic and land use dimension lacking in Britain, as reflected in the following definition:

The aim is to create a more rational territorial organization of land use and the linkages between them, to balance demands for development with the need to protect the environment, and to achieve social and economic objectives (Wegener, 1998). Spatial planning tries to coordinate and improve the impacts of other sectoral policies on land use, in order to achieve a more even distribution of economic development within a given territory than would otherwise be created by market forces. Spatial planning is, therefore, an important function for promoting sustainable development and improving quality of life.

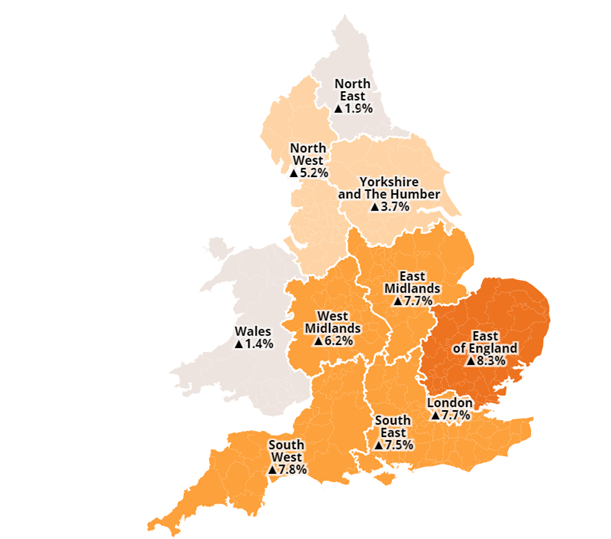

Here the term is sometimes used interchangeably with strategic planning or regional development and its role has now been partly taken over by the UK government’s concept of ‘levelling up.’ Nevertheless, Royal Town Planning Institute-accredited master’s degrees in spatial planning are offered by a number of universities in England and Wales, including University College London’s Bartlett School. Unequal development between regions is reflected in the following census map which shows rates of population growth between 2011-21 based on Office for National Statistics data (Source: Transport for the North blog)

Severn Regional Growth Zone

Spatial planning in the English West Midlands and South West regions of SRGZ (and other growth areas) has been dominated since the 2000s New Labour Regional Spatial Strategies by housing-led development but without tackling the root causes of supply-side and market-driven shortages at a national (or sub-national) level. In the meantime, increasing urban sprawl has made parts of the country among the most vulnerable to flooding even more so. The proposed SRGZ is in some respects a worthy attempt to promote a more integrated regional development model, particularly with regard to reducing flood risk. For instance, the latest iteration of the Severn Valley Water Management Scheme consultation refers to ‘A Landscape Vision.’ This suggests the possibility of holistic landscape regeneration, of the kind described above, within the Severn Uplands catchment area as well the Severn Valley in Powys and Shropshire based on the existing catchment-based approach. However, such a comprehensive approach would require unprecedented levels of co-operation and co-ordination between the UK and Welsh government administrations, as well as respective lead public bodies, the Environment Agency and Natural Resources Wales; in addition to the myriad of other stakeholders. Nevertheless, there are some grounds for optimism that progress is being made.

Cambrian Regeneration Zone

Whilst the county is approximately 25 per cent of the landmass of Wales, it has only five per cent of the population. The population in Powys is older compared to the rest of Wales and the proportion of older people is growing. The working age adult population is smaller compared to the rest of Wales and it is predicted that the number of young people and working age adults will decrease, whilst the number of older people will increase. It is predicted that there will be an eight per cent decline in the Powys population by 2039. (Paragraph 1)

Although 2021 census data casts doubt on whether the final sentence is actually correct – the county is now forecast to have a small increase in population by the early 2040s – the demographic contrast with projections for neighbouring Shropshire is still quite remarkable. Moreover, the Ceredigion area experienced a 5.8% decline in population between 2011-21, the largest in Wales. Given the demographic challenges posed by Mid and West Wales, in 2020 the author of this blog proposed a Cambrian Regeneration Zone for Powys and Ceredigion based on enhanced investment in rail, energy and digital infrastructure to help rebalance and level up the regional economy and encourage working age adults to remain and come to live in the region. A landscape regeneration vision for the Cambrian Mountains was also put forward as a key part of the programme. Meanwhile, a monumental scheme for a Powys Crematorium was submitted by a local developer with the backing of the County Council, but later refused planning consent by the Welsh Government because the proposed location was unsustainable for its operation.

Integrated Regeneration Model

Some of the challenges for integrating landscape with built environment and spatial regeneration have been described above. Aside from technical issues, those of governance and management are central. Even in a relatively well regulated ‘environment’ such as the UK, there are significant problems with governance and implementation of standards. This was highlighted recently when the UK government’s progress with environmental targets was called in to question by non-government organisations. Added to this is the tendency for land-based sectors, including agriculture, property and construction to be regulation-averse in various ways. Public watchdogs have also been weakened by successive governments with their remits increasingly laissez-faire, leading to major problems across built, green and blue environments from the cladding scandal to river pollution. Whilst professions bodies such as the Royal Town Planning Institute and Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors are fully aware of problems within their respective areas of responsibility, there is a tendency for the public and private sectors to use gaslighting strategies when difficult questions are raised. Therefore, the starting point for better integration of regeneration models is likely to be greater transparency, political accountability and effective communication.

Post-War Recovery in Ukraine

Since April 2022, the British architect Norman Foster has been working with stakeholders in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv on a ‘reconstruction masterplan approach’ A recent update states: “This urban design project, commissioned by the city of Kharkiv, will be undertaken by the Norman Foster Foundation in Madrid and the Arup office in Berlin, working in collaboration with local architects and city authorities.” The approach described suggests a combination of influences from European post-war reconstruction, post-industrial urban regeneration and contemporary visions for sustainable development, plus considerable public engagement. However, international and Ukrainian environmental and natural conservation organisations also advocate a ‘green post-war recovery,” with the World Wildlife Fund calling in September for a “sustainable, climate and nature positive reconstruction” The latter would require the integrated regeneration model discussed above, and it is not without some tragic irony that the profound challenges of Ukraine’s post-war recovery may perhaps create the right conditions for the fuller emergence of a regenerative sustainability paradigm. However, this prospect in still a long way off and in the meantime there remain many battles to be fought.

well thought out and is an inspiring document, to be read by all who have a duty to, and all those, who care for our natural envirnoment

LikeLike