Introduction and Summary

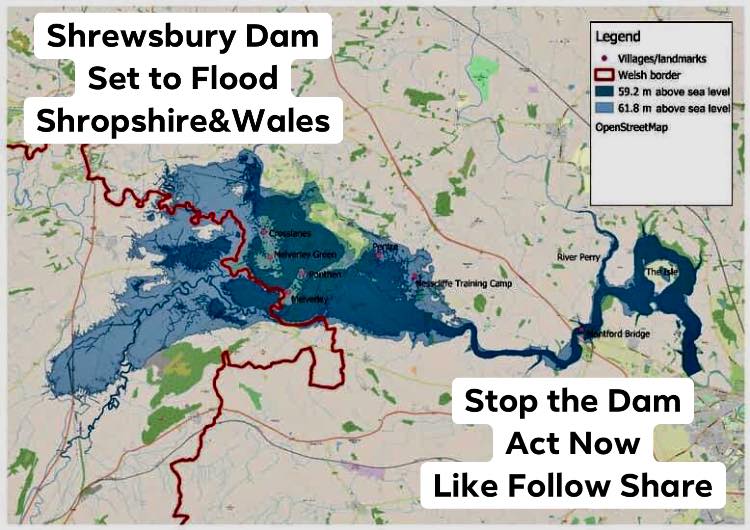

In early December 2020, the Environment Agency (EA) opened a three-year consultation on “water management of the River Severn.”(1) This announcement came as a welcome development to local action group “Save Our Severn” (SOS) who had been campaigning for several months against proposals for a “dam” to the north of Shrewsbury and in favour of a “long-term, sustainable solution to flooding.”(2) By mid-February 2021, the EA had dropped its preferred option for the water management scheme – in effect a dam combined with the largest reservoir and wetland of its kind in England – integrated with Shropshire Council’s proposed Shrewsbury Northern Relief Road. Nevertheless, later that month Shropshire Council submitted a planning application (to itself) for the road scheme.(3) The “integrated transport and water management scheme”, as it is described in the River Severn Partnership’s prospectus for a “Severn Regional Growth Zone,” goes back to the 2000s, and predates the broader catchment-based approach to management of the Severn Basin.(4,5,6) The environmental polemicist George Monbiot maintains that “you can judge the state of a nation by the state of its rivers.”(7) As the world enters the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-30), the account below of a range of options – from re-engineering to rewilding – for water management in the Severn Valley also offers some perspectives on the state of nature conservation and recovery in England and Wales.(8)

This article is structured as follows:

- Key issues for the Severn Valley: connectivity, flooding, drought, pollution, development

- Environmental governance: new River Severn Partnership and stakeholder engagement

- Different approaches to water management: catchment-based to infrastructure options

Major issues for the Severn Valley and Severn Uplands Catchment Areas

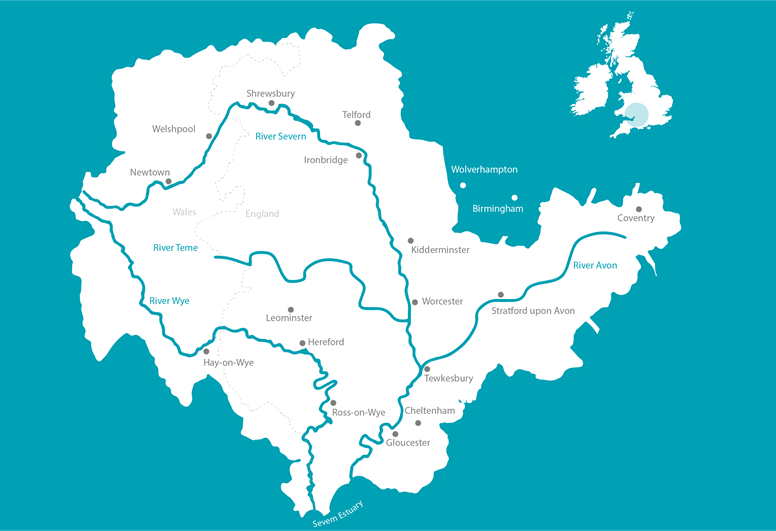

There have previously been questions about the geographical scope of the Severn Valley Water Management Scheme (SVWMS) An earlier “Frequently Asked Questions” information sheet described its “focus” as “towards the top of the River Severn catchment”. This statement encapsulated a certain vagueness about the project and the relationship of SVWMS to RSP’s preferred option of the integrated transport and water management scheme to the north of Shrewsbury as well as to the catchment-based approach for managing the Severn Basin as a whole. Moreover, although the “Severn Valley” is often taken to mean the river corridor between Bridgnorth in Shropshire and Bewdley in Worcestershire the following discussion highlights the relevance of the Severn Uplands Catchment. This covers a large area from the source of the River Severn in Wales to Oswestry in the north, Shrewsbury in the east and southwards to the English Severn Valley, providing vital connectivity which is discussed below.(9)

As Britain’s longest river straddling England and Wales, the Severn represents a significant barometer for the wellbeing of the natural environment and its relationship with agricultural and urban hinterlands. However, since the turn of the century this relationship has tended to be dominated by major flooding, with increasingly regular events culminating in the inundations of February 2020 of which Shrewsbury was one of the epicentres.(10) A political imperative to prioritise “flood resilience” has deflected attention and, more importantly, resources away from pollution of English rivers for which the EA last year published alarming water quality data.(11) Combined with these problems is that of periodic water shortage and drought in the Severn Basin, sometimes following months of heavy rain and flooding as in 2020, or exceptional snowfall in the case of 2018.(12) These extremes, as well as increasing pollution, pose significant challenges for some wildlife, notably Atlantic Salmon for whose protection the UK Government has introduced an emergency byelaw covering the Severn and its estuary.(13) Another key requirement for salmon and other wildlife is the connectivity provided by the Severn and rivers in its catchment area. “Unlocking the Severn” is a project whose aim is to enhance connectivity through restoring river habitat and providing fish passages through weirs.(14) The project is designed to encourage active stakeholder and community involvement in restoration work. This vital because the English Midlands Severn region is home to several million people and there are plans for significant growth and new development.(5)

Nevertheless, EA data indicates that around 80% of the river basin district land is used for agriculture and forestry.(6) Although Natural England provides guidance on “Catchment Sensitive Farming” for the Severn River basin and others(15), “rural land management” is the major contributor to river pollution, followed by a mysterious “no sector responsible” and then by the water industry.(6) Philip Dunne, Conservative MP for Ludlow and chair of the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, has responded to the latter offenders by launching a private member’s bill to tackle river pollution from untreated sewage. The Sewage (Inland Waters) Bill was developed in consultation with NGOs such as the Rivers Trust, Salmon and Trout Conservation, and the Angling Trust.(16) At its launch, the MP declared: “The River Severn and its tributaries the Clun, Corve, Kemp, Onny, Rea, Teme and Worfe all flow through my constituency. They are nothing like as healthy as when I was a child, but they should be.” This initiative is an important reminder that pollution is a major challenge for the Severn Valley and Uplands, requiring a higher profile in water management schemes proposed here and elsewhere. Recent EA data shows that only 16% of England’s freshwater bodies (rivers, lakes and streams) are deemed to be in good ecological condition, compared to 46% in Wales and 65.7% in Scotland.(17) This obviously has significant adverse implications for nature conservation and recovery.

Environmental governance and potential roles of the new River Severn Partnership

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature defines environmental governance as “the means by which society determines and acts on goals and priorities related to the management of natural resources.” It includes “rules, both formal and informal,” and “appropriate legal frameworks on the global, regional, national and local level.”(18) In 2020, the UK Government published a policy paper on environmental governance as part of the Environment Bill. This legislation aims to “drive significant environmental improvement by setting and achieving legally-binding, long-term targets on air quality, water, biodiversity and resource efficiency and waste reduction, as well as through statutory Environmental Improvement Plans.(19) The development of such a plan (or plans) for the Severn Basin Catchment Area would seem to be a multi-agency role ideally suited to the River Severn Partnership, created in 2019 with the Environment Agency as one of its lead organisations, the other being Shropshire Council.(4) RSP also includes Natural Resources Wales, with the potential to deliver cross-border environmental improvements.

However, the partnership’s mission to support ambitious growth plans in Shropshire and the Severn corridor through the English Midlands, including the UK Government’s house-building targets, suggests that it may be difficult, if not impossible to strike a balance between economic development and environmental sustainability.(5) Indeed RSP’s proposed Severn Regional Growth Plan whose current flagship project remains the integrated transport and water management scheme – or Shrewsbury Northern Relief Road, dam, reservoir and wetland – seriously alarmed local communities towards the top of the Severn Catchment across England and Wales. As a result of concerted campaigning against the “Shrewsbury dam” by local action group Save Our Severn and others during the Autumn of 2020, RSP embarked on the three-year Severn Valley Water Management Scheme consultation. This extended period is intended to enable proper engagement with communities affected by the proposal and consideration of a range of alternative options (see below). RSP’s membership also includes statutory and non-governmental nature conservation groups, including Natural England, Local Nature Partnerships, the Wildlife and Severn Rivers Trusts. The latter are champion of a catchment-based partnership approach to management of the Severn which does not compromise the river’s important connectivity for wildlife and lends itself to a “long-term, sustainable solution to flooding” of the kind sought by SOS.(20) Key to this approach will be inclusion of the Severn Uplands catchment in Wales in scoping nature-based solutions to developing flood resilience such as rewilding.(21) Nevertheless, continued pressure from RSP stakeholders primarily concerned with economic sustainability will mean that engineering – or re-engineering – solutions to water management remain an option.

Optioneering* different approaches to water management in River Severn Catchments

In June 2020, MP for Shrewsbury and Atcham Daniel Kawczynski announced the establishment of an all-party group of MPs whose constituencies are affected by flooding of the River Severn. He expressed the view that: “… hitherto, it’s been a very piecemeal, sporadic approach where, every now and again, small-scale flood defences have been put in place, but this has just moved the problem further down the river,” and “the approach I want to see involves managing the whole river, and that will require more flood investment.”(22) Whilst Kawczynski appeared to back the Shrewsbury integrated transport and water management scheme, his statement also acknowledges the need for a catchment based approach to managing the Severn Basin. It is possible that the MPs’ consortium could fulfill the role of a commission to consider different approaches to river management and thereby bring greater public accountability to the work of the River Severn Partnership. An announcement at the end of 2020 that the new Office for Environmental Protection is to be headquartered in Worcester also offers new hope that environmental challenges facing the River Severn will be in future be subject to additional scrutiny.(23)

Rural land management is obviously fundamental to managing flood risk at the catchment level although it is unclear to what extent. In response to the intense flooding of 2000 at Shrewsbury and elsewhere along the river, English Nature (later Natural England) published an extensive report entitled “Modelling the effect of land use change in the upper Severn catchment on flood levels downstream” (2002).(24) However, the findings were somewhat inconclusive and this tended to be the case for research in the following decade, leading the Houses of Parliament Office for Science and Technology to state in 2014 that: “A lack of empirical evidence on the effectiveness of catchment-wide approaches is a barrier to their implementation.”(25) Yet within a couple of years, discourses around rewilding seem to have moved forward institutional thinking on what has become known as natural flood management. For instance, writing in ECOS (37/1 2016), Steve Carver argued in favour of this approach (26), as did Alastair Driver of Rewilding Britain (and formerly the Environment Agency) in the same year.(27) Yet, whilst support for natural flood management has grown since then, large-scale implementation of the kind required for a catchment-wide approach in the Severn Valley and Uplands has been limited, not least by the availability of public funding. To illustrate, in July 2020 the Welsh Government allocated some £2 million to 10 schemes across the country, including a project at the headwaters of the River Severn in the Cambrian Mountains.(28) This compares with £5.4 million provided by the UK government for “carbon offsetting” and nature-based approaches to flood resilience along the Severn in England earlier this year (29) A prior example of the type of small-scale initiative enabled by this level of funding is “Slow the Flow”, a 6-year programme involving Shropshire Council, the Environment Agency and Shropshire Wildlife Trust in the Middle Severn Catchment area.(29) The Trust hosts the catchment partnership for this section of the river, along with Severn Rivers Trust, and a plan for 2017-20 explains the approach to its management.(30)

To put this approach and the resources available to it in context, it’s useful to return now to the proposals for the Severn Regional Growth Zone and its flagship project of a relief road and dam across the river to the north of Shrewsbury. The gestation of this project also goes back to the 2000s as explained in an Environment Agency Pre-Feasibility Report of 2009 entitled Severn Valley Flood Risk Management Phase 2.(31) In 2002, the Environment Agency collaborated with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, English Nature (Natural England), Shropshire Wildlife Trust, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and the former Countryside Agency to create ‘The Upper Severn Wet Washlands Option Group’. The group’s mission was to identify locations along the Upper Severn Valley suitable for wetland habitat creation, or ‘Wet Washlands’, as a means of flood mitigation. In 2005, this exercise concluded that the most suitable location for the development of a wet washland was in the natural River Severn floodplain immediately upstream of Shrewsbury. The scheme’s major opportunities were identified as: the creation of approximately 200 hectares of new wetland habitat and reduction of flood risk to properties in Shrewsbury and further downstream (possibly as far as Worcester). Major constraints were described as: flood risk to properties upstream of the flood control structure (within the wet washland area), the potential negative impact of the control structure on the river’s ecological status and migratory fish, and on the existing landscape. Then in 2009 Shropshire County Council commissioned further feasibility work with the purpose of determining the ‘combined’ economic business case for the ‘flood control structure” co-located with the proposed Shrewsbury Northern Relief Road’ scheme.

During the next decade, not much progress seems to have been made on either the flood control structure or road scheme, whilst a range of “sporadic”, “piecemeal” and “small scale” “flood defences” – to use Shrewsbury MP Daniel Kawzsynski’s words – have been implemented within the broader catchment-based approach to the Severn Basin. The creation of the River Severn Partnership in 2019, followed by major flooding in 2020 and the impetus to “Build Back Better”(32) provided by the Coronavirus pandemic have not only regalvanised the Shrewsbury project but also transformed the context for this. As previously emphasized, facilitating economic development is RSP’s central mission. To enable this, other key aims include: “ensuring infrastructure and future infrastructure investment resilient to climate change” and “to contribute to wider environmental objectives – assisting future water security for sector-based growth and (to) explore the potential for energy generation initiatives.”(32) RSP has received £40 million of government funding(29), and is now seeking £9.7 million to produce a masterplan for the Severn Regional Growth Zone which integrates economic development and broader place-based objectives together with a project implementation programme to attract wider investment.(5) A core governance and organisational aim is to “create system level stewardship across Britain’s longest river network, with a shared commitment to delivering environmental and biodiversity gains…” According to its prospectus, the SRGZ will provide a “national pilot and showcase, focussing on interdependencies between water, as a key natural asset, and the wider delivery of housing, employment, skills, transport and green infrastructure.”(5)

As RSP and SRGZ’s flagship project, the Shropshire integrated transport and water management project very much embodies this growth vision. It’s blue/green infrastructure component is described as “a large-scale water and wildlife resource between Shrewsbury and Oswestry which could potentially be of national significance”(33) In pursuit of the “resource”, the RSP “have engaged with (the) Shropshire Wildlife Trust and Natural England and are engaging Eden Project International (Eden Project Cornwall) who are extremely interested in working with the Partnership …This also offers a significant economic opportunity for Shropshire.” Yet notwithstanding the prospective interest of “Big Conservation” groups, at one time also including the RSPB, RSP’s erstwhile preferred water management option provoked widespread opposition among a range of stakeholders. Some of these, including local farmers and community-based organisations, like Save Our Severn, raised substantial concerns about the proposal’s environmental impact.(34) By way of alternative, CEO of the Severn Rivers Trust, Mike Morris, expressed the strong preference for a regional or catchment-based approach of “working with natural processes to reduce flood risk rather than building ever higher walls that act as a “sticking plaster” and that may have negative impacts on the river and its species.”(35)

The current 3-year consultation on the Severn Valley Water Management Scheme provides a window of opportunity for RSP to revisit a range of options for developing flood resilience in the area previously identified by the Environment Agency as “towards the top of the River Severn catchment”. These could include the creation of a so-called washlands across the border in Wales, as suggested by Chair of the Welsh Conservatives, and former MP for Montgomeryshire, Glyn Davies. During localised flooding caused by snowmelt in late 2017, he commented: “The acres of land under water (at Welshpool) are better than flooding Shrewsbury, Tewkesbury and other towns further south.”(36) Indeed, the very name Welshpool – or Y Trallwng meaning “the marshy or sinking land” – evokes a large wetland of the kind sought by RSP. Mr Davies, however, was addressing the need for flood resilience in the English Midlands to be considered in the broader context of the Upper Severn Catchment; and referencing, in particular, the Montgomeryshire Wildlife Trust’s Pumlumon Project of which he is a long-term supporter.(37) This is a large upland ecological restoration project in Mid Wales summarised in the then Westminster MP’s blog – A View from Rural wales – as follows:

The Pumlumon Project… relates to 100,000 acres within the triangle stretching between Llanidloes, Machynlleth and Aberystwyth, where the Rivers Severn, Wye and Rheidol begin their journeys to the sea. The project involves re-wetting the peat bogs, and connecting existing habitats to create natural pathways. This would, if done at scale, hold back enormous amounts of rainwater and melting snow, preventing flooding further down the Severn Valley. At the same time give more support to viable communities, create more natural landscapes, a more diverse wildlife, cleaner water and store carbon.(36)

Mr Davies also pointed out the achieving this vision would require UK Government funding.

Some concluding reflections on flood resilience and opportunities for nature recovery

In September 2020, research by the Natural History Museum concluded that the “UK has led the world in destroying the natural environment” with “the key driver of biodiversity loss” being “land-use change” linked to agriculture and urban development.(38) Then on 5th November, the UK government issued a “call to action” for “tackling three of the biggest challenges we face: biodiversity loss, climate change, and people’s isolation from the natural world.”(39) Led by Natural England, the Nature Recovery Network Delivery Partnership includes some 600 organisations and a key aim is to “recover threatened animal and plant species and create and connect new green and blue spaces … by providing more habitat and wildlife corridors to help species move in response to climate change.” Another core mission of the partnership is to “bring nature much closer to people, where they live, work, and play, boosting health and wellbeing”. This announcement followed a widely publicised call by Rewilding Britain in the previous month for a “rewilding network” with similar aspirations to the government-led initiative to “tackle the climate emergency and extinction crisis (and) reconnect people with nature.”(40) These initiatives provide an important new context for issues relating to the Severn Basin, and particularly for the area towards the top of the River Severn Catchment. Moreover, although the writer is not an aficionado, a recent symposium organised by Rewilding Europe suggests the movement may now hold an emerging opportunity for institutional transformation.(41)

My own particular interest in the Severn goes back some twenty years, first as a resident of Worcester and now as someone who lives a mere stone’s throw from the river in Caersws, Powys. I also have a professional interest in spatial planning and, in particular, options assessment processes – or “optioneering” – at both the strategic and project levels.In my – now rather long! – experience scheme promoters tend to identify a preferred option before full comparative studies have taken place, notwithstanding statutory requirements for environment assessments that require alternative options to be considered. A key factor in the identification of spatial options is the scope of the study area and this issue is especially relevant to the Severn Valley Water Management Scheme. The extent of the Severn Valley, including the river corridor in Wales, needs to be clearly defined by the River Severn Partnership, and the scope of the wider study area incorporating the Severn Uplands made explicit.(10, 42) A long list of options – from a landscape re-engineering solution such as Shrewsbury dam (shorthand description) to landscape scale (or perhaps bioregional(43)) natural flood management, for instance – then needs to be assessed against clear aims and objectives. A transparent assessment process which engages stakeholders at different stages is essential if there is to be any ultimate consensus on what in the case of SVWMS will be a preferred options package, rather than one solution. The approach known as TINA – “There Is No Alternative” to a preferred option arrived at prematurely – usually meets with major opposition, as RSP have found. Optioneering and consultations undertaken between 2016-18 by the Environment Agency for the Rivers Ouse and Foss in Yorkshire demonstrate comprehensive and holistic approaches to flood resilience are available.(44,45)

One of the biggest obstacles to developing a “long-term, sustainable solution to flooding” of the kind sought by Save Our Severn lies in the funding settlement between the UK and Welsh governments and their respective agencies, the EA and Natural Resources Wales. The problem has been clearly articulated by Welsh Conservative Chair Glyn Davies.(36,37) However, challenges run deeper than funding. The water politics of the 20th century – embodied in opposition to the construction of reservoirs in Wales to supply England – proved one of the most divisive issues in cross-border relations. This has a legacy in Welsh resistance to changes in rural land use and resource management regimes proposed by organisations regarded as English.(46) Currently, resistance is also found across the border in England to the new Control of Agricultural Pollution Regulations introduced by the Welsh Government with effect from 1 April 2021.(47,48) These controversies only re-enforce the need for co-operation. Given its predominantly English focus, it must be open to question whether the River Severn Partnership can bridge such difficulties. A Severn Valley water management commission or review with cross-border representation may be required to work in parallel to the Environment Agency. Both the EA and NRW also have internal funding and human resource constraints making enforcement of pollution regulations, for instance, difficult and these constraints might be considered by an independent group.(49)

In January 2021, there was more serious flooding in the English Severn Valley, with towns in Shropshire again badly hit. Although there may be differences of opinion about the best approaches to flood resilience along the River Severn, there is a consensus that something needs to be done on a large-scale. Fortuitously perhaps, the area in question, including Montgomeryshire or North Powys, might be described as Tory heartlands or even “Blue Wall.” Identifying a package of solutions for water management in a broadly defined Severn Valley therefore provides a major opportunity for the new brand of Green Conservatism embraced by the UK Government. Whilst this needs to include a public funding settlement with the Welsh Government, it can also include innovative private finance, both philanthropic and commercial, as so-called natural capital is increasingly represented in economic calculations.(50) Indeed, the challenge of water management along the River Severn provides an ideal case study for the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-30) with the potential to defragment nature recovery efforts across England and Wales and, perhaps, for the UK to lead the world in restoring the natural environment.(51)

*Note on Optioneering – Two November 2020 reports by the UK National Audit Office point to the importance of optioneering – the process by which options are generated and assessed – for both major programmes and projects (52). “Achieving government’s long-term environmental goals” and “Lessons learned from major programmes” both highlight the need for transparent aims and objectives, proper scoping of initiatives, clear oversight and co-ordination, and arrangements for monitoring, learning and improving. Appropriate stakeholder engagement throughout the programme and project development and implementation process is also essential.

References

1. Environment Agency Severn Valley Water Management Scheme consultation page https://consult.environment-agency.gov.uk/west-midlands/svwms/

2. Save Our Severn action group https://saveoursevern.com/

3. River Severn Partnership http://www.riversevernpartnership.org.uk/

4. Shropshire Council Shrewsbury North West Relief Road https://www.shropshire.gov.uk/roads-and-highways/shrewsbury-north-west-relief-road

5. Shropshire Council/River Severn Partnership – Severn Regional Growth Zone prospectus http://riversevernpartnership.org.uk/media/rtbfy3e0/appendix-a-unlocking-the-severn-regional-growth-zone.pdf

6. Severn River Basin District Catchment Data Explorer https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/RiverBasinDistrict/9 Catchment Based Approach https://catchmentbasedapproach.org/

7. George Monbiot, The Guardian 12.8.20 The government is looking the other way whilst Britain’s rivers die before our eyes https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/12/government-britains-rivers-uk-waterways-farming-water-companies

8. UN Decade on Ecosystems Restoration https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/

9. Catchment data explorer Severn Uplands Management Catchment https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/ManagementCatchment/3076

10. Wikipedia 2019-20 United Kingdom floods https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019%E2%80%9320_United_Kingdom_floods

11. University of Birmingham 15.10.2020 All of England’s rivers are polluted – revealing the “invisible water crisis” https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/thebirminghambrief/items/2020/10/all-of-england%27s-rivers-are-polluted-revealing-the-%27invisible-water-crisis%27.aspx

12. UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 11.6.2020 From severe flooding to drought conditions in a matter of weeks https://www.ceh.ac.uk/news-and-media/news/severe-flooding-drought-conditions-matter-weeks

13. UK Government press release 15.6.2020 Emergency byelaw to protect Severn salmon stocks extended https://www.gov.uk/government/news/emergency-byelaw-to-protect-severn-salmon-stocks-extended

14. Unlocking the Severn https://www.unlockingthesevern.co.uk/

15. Natural England Publications Catchment Sensitive Farming Severn River Basin District Strategy 2016-21

16. Sewage (Inland Waters) Bill 2019-20 https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8820/

17. Water Briefing 18.9.2020 Latest Environment Agency data reveals all English rivers fail pollution tests https://www.waterbriefing.org/home/regulation-and-legislation/item/17601-latest-environment-agency-data-reveals-all-english-rivers-fail-pollution-tests

18. International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Environmental Law – Governance and MEAS https://www.iucn.org/theme/environmental-law/our-work/other-areas/governance-meas#

19. UK Government 10.3.20 (updated 21.10.2020) Environmental governance factsheet (Parts 1 & 2) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environment-bill-2020/10-march-2020-environmental-governance-factsheet-parts-1-and-2

20. Shropshire Middle Severn Partnership Catchment Plan https://www.shropshirewildlifetrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-12/Shropshire%20Middle%20Severn%20Catchment%20Plan.pdf

21 Severn Uplands Catchment Partnership Catchment Plan 2017-20 https://catchmentbasedapproach.org/get-involved/severn-uplands/

22. Shropshire Star 10.6.2020 MP sets up group to tackle flooding https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/environment/2020/06/10/mp-sets-up-group-to-tackle-flooding/

23. Interim CEO appointed for Office for Environmental Protection 28.1.2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/interim-ceo-appointed-for-office-for-environmental-protection

24. Natural England Access to Evidence – Modelling the effect of land use change in the upper Severn catchment on flood levels downstream (ENRR471) 2002 http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/62095

25. UK Parliament Research Briefing December 2014 Catchment-wide Flood Management https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pn-484/

26. Steve Carver ECOS (37/1 2016) Flood management and nature: can rewilding help? https://www.ecos.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ECOS-37-1-32-Flood-management-and-nature.pdf

27. Rewilding Britain 2016 Reduce flood risk through rewilding says report https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/blog/reduce-flood-risk-through-rewilding-says-report Rewilding-Britain-Flood-Report-Sep-6-16.pdf

28. Welsh government press release 24.7.2020 More than £2 million for natural flood management schemes across Wales https://gov.wales/more-than-2million-natural-flood-management-schemes-across-wales

29. Environment Agency 17.7.2020 River Severn Partnership secures over £40 million boost for flood defence https://www.gov.uk/government/news/river-severn-partnership-secures-over-40m-boost-for-flood-defence

30. Shropshire Council Slow the Flow! https://www.shropshire.gov.uk/drainage-and-flooding/policies-plans-reports-and-schemes/slow-the-flow/

31. Environment Agency June 2009 Severn Valley Flood Risk Management Phase 2 Pre-feasibility Report Phase 2 Final http://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2010-0588/DEP2010-0588.pdf

32. Let’s Build Back Better speech by COP26 President Alok Sharma 3.8.2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/lets-build-back-better CBI article 2.11.2020 Build Back Better https://www.cbi.org.uk/articles/build-back-better/

33. Shropshire Council Cabinet Report 27.9.2020 River Severn Partnership – Shropshire Flood prevention https://shropshire.gov.uk/committee-services/documents/s25231/a%20River%20Severn%20Partnership%20Report_%20002.pdf

34. Farmers Weekly Rhian Price 8.1.2020 River Severn dam proposals “could decimate farms” https://www.fwi.co.uk/news/environment/river-severn-dam-proposals-could-decimate-farms

35. Save Our Severn Facebook page on 2.11.2020 references October 2020 report in Salmon and Trout Magazine quoting Mike Morris, CEO of Severn Rivers Trust https://www.facebook.com/SaveOurSevern/

36. Sue Austin Shropshire Star 19.12.2017 How Welsh fields could halt Shropshire flooding https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/farming/2017/12/19/welsh-answer-to-englands-floods/

37. Glyn Davies (Chair, Welsh Conservatives, former MP for Montgomeryshire) A View from Rural Wales blog post 4.1.2018 http://glyn-davies.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-pumlumon-project.html Montgomeryshire Wildlife Trust Pumlumon https://www.montwt.co.uk/projects/pumlumon-project

38. Natural History Museum News 26.9.202: UK has “led the world” in destroying the natural environment https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2020/september/uk-has-led-the-world-in-destroying-the-natural-environment.html

39. UK government press release 5.11.2020: “Biggest ever nationwide initiative to restore nature in England set for launch” https://www.gov.uk/government/news/biggest-ever-nationwide-initiative-to-restore-nature-in-england-set-for-launch

40. Rewilding Britain press release October 2020: “New network to spearhead rapid rewilding across Britain” https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/news-and-views/press-releases-and-media-statements/new-network-to-spearhead-rapid-rewilding-across-britain

41. Rewilding Europe 3 December 2020: Connecting Rewilding Science and Practice Online Symposium https://rewildingeurope.com/news/symposium-success-reveals-huge-potential-of-rewilding/

42. Natural Resources Wales, Severn Valley National Landscape Character Assessment, March 2014 https://naturalresourceswales.gov.uk/media/682582/nlca19-severn-valley-description.pdf

43. Ecology and Society feature 2017: The Politics, Design and Effects of a Bio-Regional Approach: The Case of River Basin Organisations https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/issues/view.php?sf=116

44. Environment Agency Capita AECOM July 2017 Slowing the Flow in the Rivers Ouse and Foss https://consult.environment-agency.gov.uk/yorkshire/slowing-the-flow-in-the-rivers-ouse-and-foss-a-lon/supporting_documents/York%20Slowing%20the%20Flow%20Report.pdf

45. Environment Agency August 2018: Slowing the flow in the rivers Ouse and Foss: a long-term plan for York https://consult.environment-agency.gov.uk/yorkshire/slowing-the-flow-in-the-rivers-ouse-and-foss-a-lon/results/slowingtheflowintheriversouseandfossasummaryofconsultationresponses.pdf

46 Powys County Times 18.6.202 RSPB Cymru takes over Mid Wales Summit to the Sea project https://www.countytimes.co.uk/news/18526360.rspb-cymru-takes-mid-wales-summit-sea-project/

47. Welsh Government 27.1.2021 Written Statement Control of Agricultural Pollution Regulations https://gov.wales/written-statement-control-agricultural-pollution-regulations

48. Shropshire Star 2.2.2021 Concerns new rules may mean more farming pollution in Shropshire https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/environment/2021/02/02/concerns-new-rules-may-mean-more-farming-pollution-in-county/

49. Will Crisp, Guardian 12.2.21 Revealed: no penalties issued under “useless” English farm pollution laws https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/feb/12/revealed-no-penalties-issued-under-useless-uk-farm-pollution-laws

50. H M Treasury 2.2.2021 Final Report – The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review

51. Environment Agency 7.7.2020 How we keep the UK’s longest river flowing to protect water supply, business and habitats https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2020/07/07/how-we-keep-the-uks-longest-river-topped-up-to-protect-habitats/

52. National Audit Office November 2020 Achieving government’s long-term environmental goals https://www.nao.org.uk/report/achieving-governments-long-term-environmental-goals/ Lessons learned from Major Programmes https://www.nao.org.uk/report/lessons-learned-from-major-programmes/